Travel Tricks 4 – Live from the Arctic!

Join us for a chat about all things travel… this time its a bit different as we are live on

I’ve had my fair share of moments where I have felt that my body has failed me. Every time I have inevitably learned that it was because I had asked it to perform outside of its normal parameters. This particular knee injury occurred on a multi-day winter hike in the Scottish Highlands and resulted in me not being able to complete the trip as planned. My hope is that by sharing this you will learn, as I have, from my mistakes. And also, how to deal with injury while in remote regions.

Let’s begin in the same format that any physiotherapist would start in your first visit to their clinic, with the context. I’ve had experience of knee injuries before as it is somewhat of an occupational hazard in my industry. My first was in late September 2020 and my body was pretty unconditioned to mountain walking after the first covid lockdown. I was living in Northern Scotland at the time, so the Nevis Range was fairly accessible, and I had my eye on a fantastic circular route just South of Ben Nevis. Called the Ring of Steal, the route is full of ascents and descents with a total 1571m elevation gain, the last descent a punishing 1050m over a rough distance of 2km. Not particularly steep in the grand scheme of descents but quite sustained. Prior to the lockdown, I was very fit and would have had no problem blasting down this hill. Neither would I have considered using walking poles. I had sufficient strength in my quads and glutes to control each step down to reduce the shock on my knees. It’s important to point out that I am very thorough at warming up and down for mountain walking, I will always maintenance stretch the working areas afterwards. However, after the first rapid 400m descent, I started feeling a stabbing pain underneath my left kneecap with each step. I began to favour my right foot for larger steps down. Soon that too began to cause me grief and added around 45 painful minutes to the hike. After a trip to the physiotherapist, I was soon training in deadlifts, squats, lunges, and core, during periods on ‘no hillwalking’. It has been my three times weekly workout regime since, and I have not suffered the same problem.

This multi-day trip was going to be most ambitious that I had attempted in the UK during winter, and the Polaris team trained hard for it. Largely consisting of deadlifts, squats, lunges, split and box squats, and step downs. Targeting the quads, hamstrings, glutes, and core. The plan was to walk from the Northern shore of the stunning Loch Affric, immediately up to the peaks that separate it from Loch Monar to the North, then West towards Kintail. We would walk the reputably epic ridgeline of the five sisters of Kintail, before heading back via the Southern side of Glen Affric. Expected trip length was 115km.

The first three days went well, if a little slowly as above 600m the snow was knee deep in most places and there was a constant windspeed of 30-35 miles an hour. These two factors made staying on our feet a constant challenge on the steep slopes. We made alterations to the route due to the slow pace and the fact that new deer fences had been erected in the Glen that would have made sticking to the intended route less feasible. The ability to be flexible with your route through mountainous regions is important because weather conditions can be different than expected on the day or other factors can make the route impassable. It’s something to constantly assess, especially in winter where the risk of avalanche is a very real possibility.

A big part of the context for this injury were my boots, which were semi stiff in the sole and designed to wear with a crampon. In of itself this is not a problem, I have had these boots a long time and I am used to wearing crampons for winter mountain walking. With this type of walking boot, the foot does not work much at all, as if it were in a ski boot, which means the muscles higher up in the thigh are working much harder. However, for the past two years I have predominantly worn bare foot or minimalist shoes for most activities, including summer mountain walking. With these boots, the foot and stability muscles are all working as intended so less stress put on the thigh muscles. Additionally, I had the added weight of a bag loaded for a multi-day winter trip. Unfortunately, I did not foresee this change in muscle use as being a problem and, perhaps naively, did not implement this change in my training.

It’s worth a note, I am an advocate for barefoot shoes because I have flat feet and there is evidence to suggest that barefoot shoes can help stabilise and make flat arches more comfortable, as well as improving balance and posture while decreasing stress on the joints. If you are interested in this, I can recommend the Vivo Barefoot Tracker Forest ESC. A fantastic boot that has a stitched sole so do not fall apart in the way Vivo’s other chemical sealed shoes are notorious for doing. They are not Gortex lined so I coat mine in leather waterproofing and dubbing wax once a week (for constant use in wet conditions).

Combine this with frequent lateral movement from dropping through the snowpack with a weight on my back and added instability from a moderate wind, it’s a perfect storm for a knee injury. Sure enough, during the third days final ascent as dusk approached, I began to feel pain on the left side of kneecap moving up the lefthand side of my thigh. Bending and straitening particularly were problematic, and this slowed our pace to the point where it was becoming clear I would not be able to continue with the team. We camped at 1111 meters and that night made a new plan to descend back into Glen Affric and double back to the car where I could make my way to Inverness and get treatment while the team continued on.

The descent was literally painfully slow. Thankfully, I have learned from previous mistakes and now take walking poles on big trips. These spread the load of your body and backpack, reducing stress on your joints and muscles, making your movement less taxing across particularly uneven terrain, great distances, or down steep descents. Though, I find they get in the way if I’m micro navigating in difficult conditions or if the terrain is so uneven that I need to use my hands, when scrambling for example. The Back Diamond Distance Carbon Z is super lightweight and very strong. They are not the cheapest, but reliability and weight are two factors I will not compromise on with walking poles.

When we reached the vehicle, my knee has swollen to the point where I feared ligament damage. These types of injuries take months to recover from and, at the time of writing this, we have upcoming expedition to the Arctic. Thankfully, after an emergency visit to the physiotherapist I learned that I had “aggravated” the sartorius muscle. This runs from the hip diagonally down across the front of the thigh to the inside of the leg and inserts just below the knee. As I have described above, the physio said probable causes where a combination of footwear type, deep snow, bag weight, and wind. After some hands-on work and ultrasound therapy, I was advised to avoid all aggravating factors until the swelling had receded, then to start gentle strength conditioning and stretches to rehabilitate the offending muscles. Meaning, no more hiking on this trip. And much sadness.

While a bitter pill to swallow, this was a valuable lesson in how to avoid this injury from reoccurring. The advice I was given was fantastic and I would like to say a big thank you for the that and the treatment I received. Importantly, I learned that due to the nature of multi-day hikes, it is advisable to give attention to the main working muscle groups to promote recovery at the end of each day, in preparation for the next day or activity. I have always known that stretching at the end of each long day is important, but so is massaging those muscle groups. In the case of the sartorius muscle, this could be buy using a water bottle applying pressure in a rolling motion on the front and left side of the thigh. This type of recovery is likened to that of athletes who compete several times over a multi-day period, which seems to me like a prudent mindset to adopt.

It’s important to accept that our bodies are not indestructible and require frequent maintenance, especially when undertaking sustained strenuous activity. It is essential to condition the body in preparation for multi-day hikes, especially in winter. Factors to be consider include are the type of terrain you’ll be covering, and therefore the boot you will wear, the weight you’ll be carrying, the length of the trip. If you are not sure how to train for this, talk to a personal trainer or a physiotherapist. Either will send you away with list of strength conditioning exercises that are appropriate for what you are doing.

Consider a remote first aid training. These are defined by a sixteen-hour course that generally covers similar content to the first aid at work but applies it to a context where you have to sustain a first aid situation for up to three hours. This is usually the maximum time in which it takes mountain rescue to get to your location in the UK, assuming you know exactly where you are. This level of training is required by all mountain leaders to take groups out in UK mountains. Each team member should carry a basic and personalised first aid kit, I would highly recommend including some ibuprofen in this. If you cannot take this because of an allergy, then speak to your GP for an alternate appropriate pain relief that has an anti-inflammatory element.

Always be prepared for something to go wrong. In the planning stage of an expedition, build escape routes into each day or travel so you have a viable means on getting you and your team safely down and back to a vehicle. Cover all of these bases, and you can take on a trip of epic proportions safe in the knowledge that if something goes wrong, you have robust procedures to fall back on to keep you and your team safe and happy.

Josh Smith

Join us for a chat about all things travel… this time its a bit different as we are live on

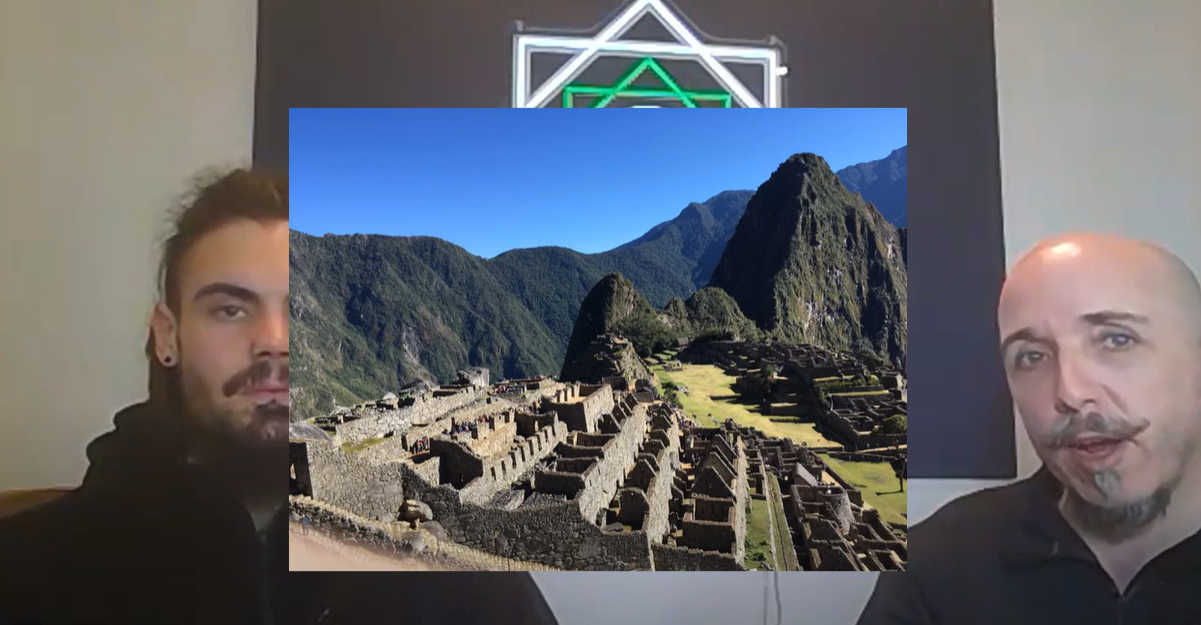

ravel Tricks Webinar 3 – Machu Picchu, Peru Edition Join us for a chat about all things travel… this time